On Mondays, R travels from the hotel where he lives in east London to a community kitchen in Waltham Forest to cook for his family.

He likes making food that reminds them of home: lentil soup with carrots, potatoes, parsley and garlic, tomatoes, aubergine, onion and green peppers fried in oil, rice, vermicelli and vegetable broth.

R, who asked to remain anonymous, came to the UK in 2022 after a difficult five-year journey across Europe from Kuwait with his wife and two children.

Since then, their family has lived in temporary catered accommodation while the government processes their asylum claims.

R said: “The Home Office gives us ready meals and [about] £1 a day.

“A lot of the food is no good.

“Without food banks and places like this [community kitchen], life would be very difficult.”

His description aligns with the findings of a recent report into the food experiences of people seeking asylum in London.

‘Dehumanising’ food experiences in the asylum system

Authored by food advocacy charity Sustain in collaboration with frontline organisations Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) and Life Seekers Aid, the report documents a grim picture.

Inedible food, inflexible meal times, nutrition-related illnesses and a routine failure to accommodate allergies and cultural or religious diets all feature.

London Food Poverty Campaign coordinator at Sustain and the report’s writer, Isabel Rice, said: “It was a lot worse than we thought, to be honest.

“There is so much injustice and indignity.

“There are a few really shocking things that will stick with me.

“It was quite difficult emotionally.”

Experiences of food in the asylum system were repeatedly described as dehumanising, with severe consequences for physical and mental health.

Rice highlighted several cases of people being hospitalised with food poisoning, malnourished infants being hospitalised and one case of a mother and baby being hospitalised because they were so malnourished.

Research participants said that catered food was particularly inappropriate for children, and parents often did not have access to a kettle and fridge to sterilise and store bottles for infants.

When someone seeks asylum in the UK, they are not allowed to work until their asylum claim has been processed.

In the meantime, the Home Office provides housing support and living expenses.

For those in catered accommodation – like R and his family – this is just £8.86 per week per person to cover all costs, including food.

Catered accommodation is supposed to be temporary but some people stay in hotels for years.

Rice said: “Impoverishing people is a deliberate part of the asylum process.

“It’s built into the policy.”

The report gives recommendations for local action while acknowledging the need for national policy change, including increasing asylum support rates, allowing people seeking asylum to work, and implementing processes to monitor whether catered food meets Home Office standards of hygiene and nutrition.

Rice also explained that even when local authorities do establish support systems and invest in community food projects, the Home Office can move asylum seekers out of the area at short notice to boroughs where there is no support in place.

Food security and community building in Waltham Forest

R and his family were living in one of two hotels housing asylum seekers in Waltham Forest when both hotels were closed suddenly in January.

400 residents were moved, with no choice over where they went.

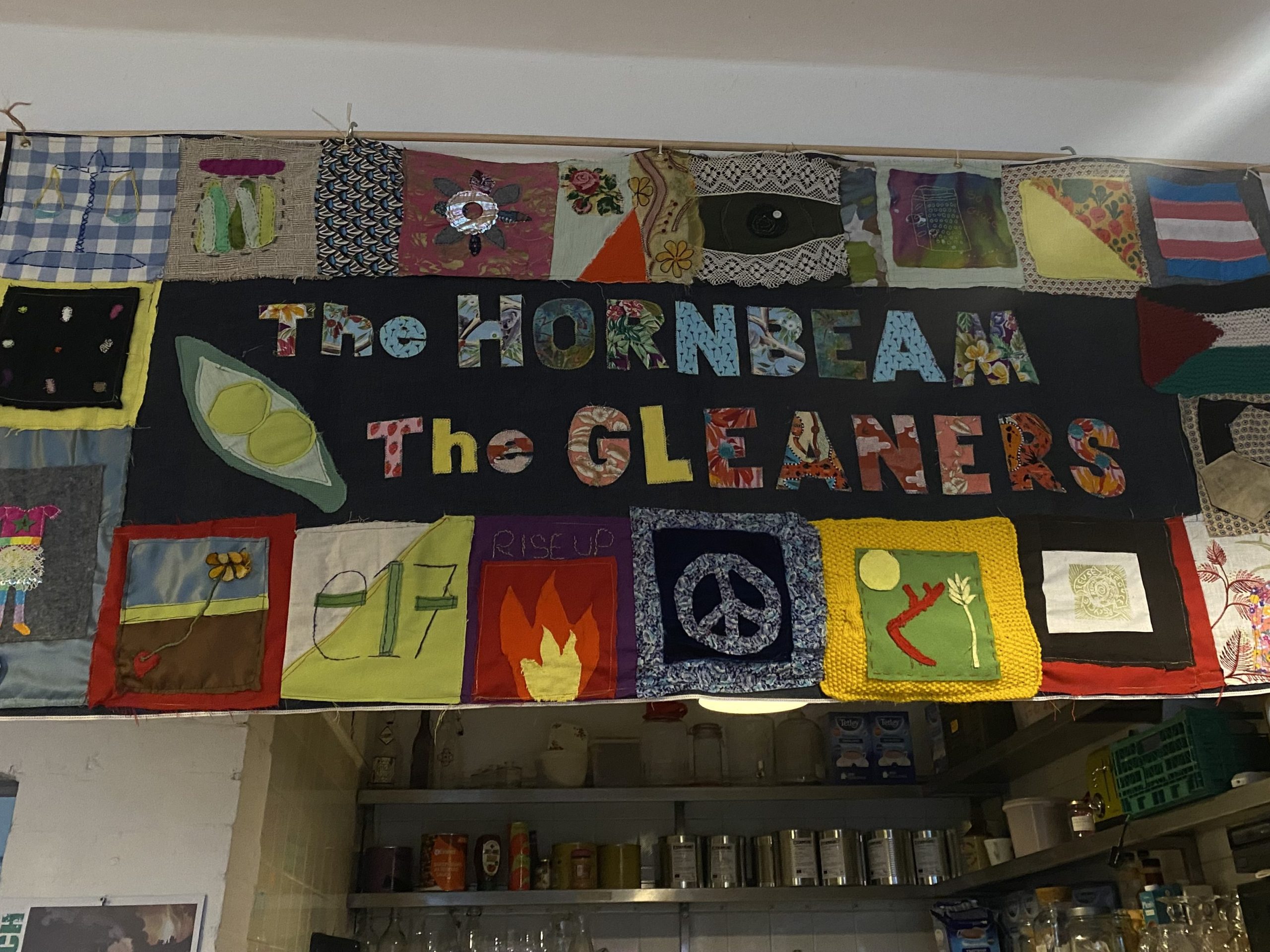

Before the eviction, families from the hotels came to the Hornbeam Centre to do bulk cooking or prepare meals for others in the hotels.

The Hornbeam is a 30-year-old community organisation that is mentioned in Sustain’s report as an example of best practice food support for asylum seekers.

The Hornbeam ran several projects for people in the asylum system, including providing ingredients and kitchen access for families on Mondays and free community meals on Tuesdays.

Some of the people who came to sessions at the centre also volunteered there, helping with food preparation and sorting crates of ingredients.

Frankie Henderson works in the yellow-fronted Gleaners Cafe on the ground floor of the Hornbeam, which uses surplus ingredients to make nutritious food on a pay-what-you-can basis.

She said: “If I came into the office on a Monday I’d be fed about four times because every single family that comes in is like, ‘Please eat with us!’”

“They’re not just chilling in the hotels.

“These are all really active and valuable members of the community.”

The Gleaners Cafe gets many of its ingredients from Organiclea, a food cooperative on the edge of Epping Forest that has worked in partnership with the Hornbeam for decades.

Organiclea also runs cooking sessions for people in the asylum system, which double as English lessons for those who need them.

Support and activities worker Marion Kent described this as “English by accident.”

Kent said: “It’s easier to talk when you’re not face to face with each other.

“Conversations tend to come more naturally when you’re focused on something else.”

The Hornbeam Centre, Gleaners Cafe and Organiclea belong to an ecosystem of small organisations addressing food insecurity in Waltham Forest, while creating spaces for community members to learn from and support one another.

These staff and volunteers are filling a void in basic food provision left by an unaccountable asylum system that is making people poor, hungry and sick.

The asylum system is subject to imminent change, but not in the direction of Sustain’s recommendations.

The Illegal Migration Act 2023, passed in July last year, could prohibit most people currently claiming asylum in the UK from having their claims heard at all.

If fully enacted, the Act would block people’s access to Home Office accommodation, leaving them at higher risk of poor nutrition, as well as homelessness and destitution.

Fewer people have attended the sessions at the Hornbeam and Organiclea since the hotels closed, but R still comes to the Hornbeam twice a week to cook and volunteer.

In fact, he was there two weeks ago when he received a text from his lawyer to say the Home Office had granted him refugee status in the UK.

It had been a long time coming and R’s hands shook as he opened the message.

R and his family left Kuwait in 2017.

They are Bedun, a stateless minority population who were not recognised as citizens when the country became independent in 1961.

Bedun are denied basic rights in Kuwait, including adequate healthcare, education and employment.

R punched the air in celebration when he realised he was getting a visa.

“They shared my happiness,” he said of the Hornbeam colleagues who were with him at the time.

“At Hornbeam, I found respect, I found help.

“Really, I found myself here.”

Responding to a BBC article about Sustain’s report, a Home Office spokesperson said: “Asylum seekers in hotels are provided with three meals a day, and additional provisions for families with a baby or toddler.

“The food provided in asylum hotels meets all the NHS Eatwell standards as well as responding to all cultural and dietary requirements.”

Join the discussion