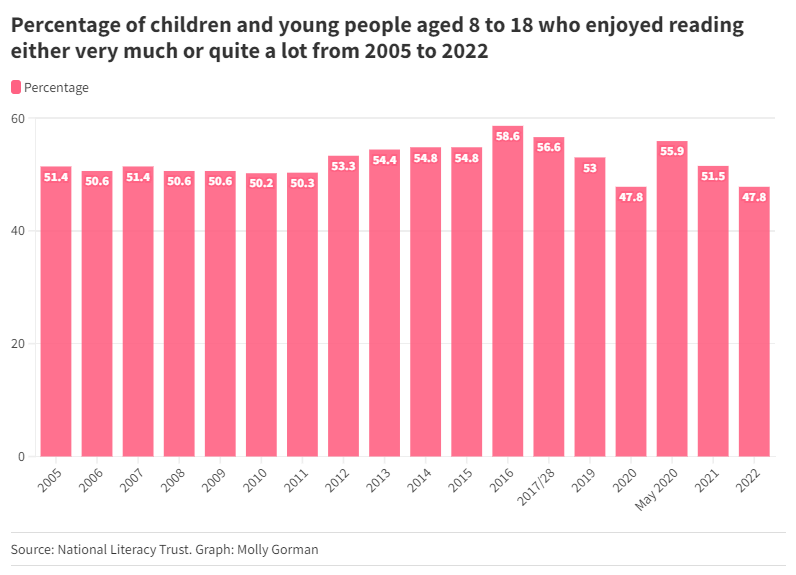

Children and young people have never enjoyed reading in their spare time less, research has shown.

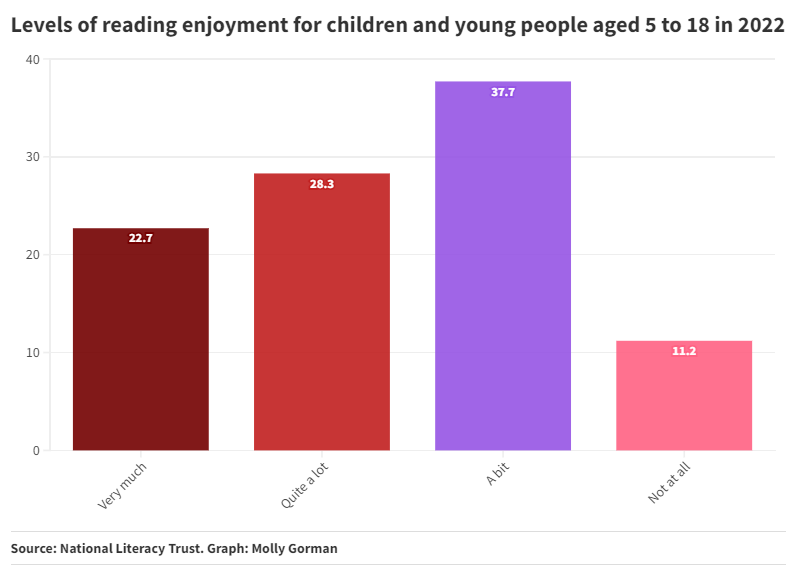

Levels of reading enjoyment were at their joint-lowest in 2022, with less than half (47.8%) of young people aged eight to 18 saying that they enjoy reading, according to a report by the National Literacy Trust.

The NLT surveyed 70,403 children and young people aged 5 to 18 from 327 schools across England, Scotland and Wales.

Dr Christina Clark, Head of Research at the National Literacy Trust, said: “Reading for enjoyment is at an all-time low, with fewer than one in two children reading for pleasure.

“This is a real cause for concern, as reading for enjoyment is linked to better reading levels at school and higher literacy levels throughout life, as well as increased mental wellbeing.

“The brief rise in reading for enjoyment in our May 2020 lockdown survey suggests that giving children and young people free time to read is vital.

“Investing in school libraries and providing a range of free, diverse books for children to choose from are just some of the ways the National Literacy Trust are supporting families and schools in the most disadvantaged areas across the country.

“It is clear that we all must do more to support children and young people with the lowest levels of reading enjoyment, and this can only happen with a holistic approach involving not just charities, but businesses, government, schools, families, and the wider community.”

The figures show that the 2022 figure has returned to the low seen in 2020, as the UK went into the first ever lockdown, then rising sharply to 55.9% in May 2020, at the height of the pandemic.

Lizzie Ineson teaches at a secondary school in Newham, East London. She thinks that children certainly enjoy reading less now than they would have a decade or two ago, which she attributes largely to technology but also the disadvantage gap.

She said: “I find that it is very unusual for children in class to have a real deep love of reading, and that would choose to do it over any other source of entertainment.

“In my class of 30, I think of maybe three children off the top of my head that would choose to read over playing on their games console/watching TV.”

There is also the issue of equal access to books. Fewer than three in 10 (28%) children and young people aged eight to 18 said that they read daily in their free time in 2022 – the second-lowest level the Trust has ever recorded.

While schools try to provide free books for children, it does not mean they are read at home. If children want new books or their own copy, it is an additional cost for parents.

Ineson mentioned the role of local libraries, which are often brilliant places for children to find books for free, but that relies on parents being motivated, or just having the time to take them there.

She added: “I work in a school which has a predominately EAL (English as an additional language) student population at approximately 70%, and this often means that parents are not first language English speakers.

“So while parents may do everything they can to support their child in their reading, they won’t be able to build their comprehension skills etc, meaning there isn’t equal access in that regard either.

“There are a lot of inequalities in terms of accessibility to books and reading, which is essentially why the disadvantage gap is widening instead of shrinking.”

Paola Minekov is an artist and mum of two living in South London. It has always been important for her and her husband to spark an interest in books and reading for their children, so they started to read to them when they were babies.

Her eldest son is an avid reader, who doesn’t leave the house without a book and can read an average book – around 200 pages – in a day.

Minekov has so far refused to buy him a kindle or tablet and prefers to buy books on paper for him, even though it’s considerably more expensive.

She said: “I wonder to what extent getting children to learn in a structured way and introducing them to technology earlier is to blame for them being less interested in reading. I’m pretty sure that given the choice, my son would rather watch animations on my phone than read a book.

“I think a lot of kids his age already have a tablet and are playing games for fun, for example. Also my generation of mums, we seem to think that our children need to be engaged and entertained all the time.

“I think we don’t allow them to get bored and find something to do like reading, self directed play, or drawing enough. If we can’t give them attention we turn the TV on or hand them a phone or a tablet.

“I’m guilty of this too but I’ve stopped doing it every time I need a minute. It didn’t make me popular in his eyes when I initially restricted television and screen time severely but he got used to it and now he reads.”

BookTrust, an organisation dedicated to getting children reading, groups the benefits of reading into four key themes. It says that children who read are more likely to:

- Overcome disadvantage caused by inequalities

- Be healthier and happier children with better mental wellbeing and self-esteem

- Do better at school and make more progress across the curriculum

- Develop creativity and empathy

New research from BookTrust found that almost a quarter of parents and carers from low-income backgrounds (23%) are not sharing books with their children before their first birthday despite the majority (95%) seeing reading as an important thing to do.

Where families are regularly reading and sharing stories together, this reaches its peak when children are between two and four years old, but the frequency of children being read to daily after the age of four drastically reduces and continues to decline throughout childhood.

BookTrust states that sharing books, stories and rhymes as a basis for playing, talking, singing and exploring in their early years provides the biggest boost to children developmentally, enhancing cognitive, physical, social and emotional growth and development during a period of significant brain growth.

Shared reading also supports bonding between children and their parents, carers or other family members; boosts parental positivity and improves children’s sleep.

Diana Gerald, Chief Executive of BookTrust said: “Reading has the potential to change lives and our aim at BookTrust is to get all children reading regularly and by choice. As this research shows, families recognise the importance of reading in their children’s early years.

“Much of this can be attributed to the hard work of early years practitioners, libraries, health visitors who we work closely with to inspire families to read and share books and stories together early on. Yet parents and carers tell us that a lack of time or confidence choosing books are the main barriers they face that prevent them from reading more.”